How the Old Masters Saw the Stars

A short primer on the basics of interpreting celestial metaphor

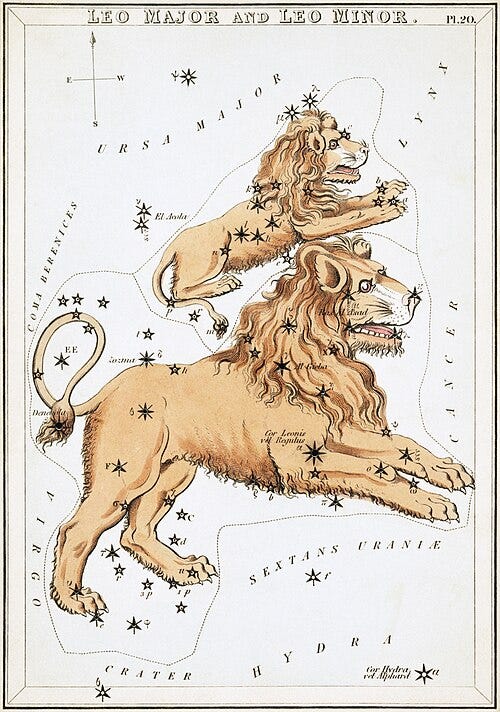

If you have ever used a modern star chart to find a constellation you probably noticed that it looked nothing like it was supposed to. Modern star charts seem to group the constellations into arbitrary geometric shapes like the example above while more classical depictions, like the example below, obscure any usefulness they might have had with their overly elaborate designs.

Writing nearly a century ago, popular esoteric author Manly P. Hall remarked that he didn’t think the constellations were ever intended to look like the figures they were purported to represent.

“There is a popular theory concerning the origin of the zodiacal creatures to the effect that they were products of the imagination of shepherds, who, watching their flocks at night, occupied their minds by tracing the forms of animals and birds in the heavens. This theory is untenable, unless the "shepherds" be regarded as the shepherd priests of antiquity. It is unlikely that the zodiacal signs were derived from the star groups which they now represent. It is far more probable that the creatures assigned to the twelve houses are symbolic of the qualities and intensity of the sun’s power while it occupies different parts of the zodiacal belt.

On this subject Richard Payne Knight writes:"The emblematical meaning, which certain animals were employed to signify, was only some particular property generalized; and, therefore, might easily be invented or discovered by the natural operation of the mind: but the collections of stars, named after certain animals, have no resemblance whatever to those animals; which are therefore merely signs of convention adopted to distinguish certain portions of the heavens, which were probably consecrated to those particular personified attributes, which they respectively represented."

(The Symbolical Language of Ancient Art and Mythology.)”- Manly P. Hall, The Secret Teaching of All Ages [Pg. 147]

It would seem that the secrets of the heavens had eluded even some of the most ardent students of astrology and myth.

A couple of decades later, the popular illustrator H.A. Rey—of Curious George fame—published a book of star charts in which he redrew the constellations to resemble the figures they were meant to represent, thereby disproving Hall and Payne Knight’s notions. The Stars a New Way to See Them is one of the most useful books I have ever read, within it Rey ingeniously simplified the night sky into a much more legible form. I highly recommend this book and Donald Menzel’s Field Guide to the stars and planets, which has even more charts based on Rey’s designs, to anyone interested in astrology, astronomy, navigation, hiking at night in the desert etc. Both books are free on Archive and are indispensable for all things star related.

While Rey makes no such claims in his book I believe that he may have stumbled upon the Old Master method, compare the outline of Virgo above with the figure in the center of Botticelli’s Primavera below.

Note the tilted head and outstretched hand, these features are typical for Virgo figures. She is often times depicted seated as below. In both paintings Cupid may have been intended as a stand-in for Bootes.

Compare this image of Demeter from ancient pottery (above) with Leonardo da Vinci’s Annunciation (below). In these images we have a Virgo figure seated with a rounded head and her hand outstretched. These both benefit from the additional context of the scene. In St. Mary’s case she has her hand on a book representative of the Coma Berenices. In both cases we have a kneeling figure likely symbolic of Bootes which hovers over Virgo. In the case of Demeter he is looking upward and offering something, characteristic of Bootes figures. In the Annunciation, the Northern Crown could be interpreted as the angel’s halo as well as parts of Hercules for the wing. Or perhaps Hercules himself is the angel as he is kneeling figure with outstretched hand, his sword could be interpreted as a wing.

An interesting feature of the constellation Virgo is the star Epsilon Virginis, formally known as Vindemiatrix which roughly translates as ‘the grape harvestress’. A curious name for the star in the Virgin’s outstretched hand. Where else have we seen a motherly figure that likes to pick fruit?

In this painting he find Eve with her hand outstretched and her head tilted, we also find a strong correlation between Adam and Bootes as the male figure is looking upward with his hand pointing. Then we have this nearby asterism ‘Serpens’, part of the greater Ophiucus constellation, which could be interpreted as the infamous serpent.

The night sky was man’s first canvas. I imagine desert nomads telling stories by the campfire at night gesturing towards the heavens, using the constellations as characters and props within their drama. The motions of the heavens and the relationships of the stars were the inspiration for many of the great myths and legends. If you can trace a piece of art back to the stars, it doesn’t get any closer to the source than that.

Works Cited & Consulted

Manly P. Hall, The Secret Teaching of All Ages (1928), Archive

H.A. Rey, The Stars a New Way to See Them (1952), Archive

Donald H. Menzel, A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets (1964), Archive

David W. Mathiesen, StarMythWorld (2015)

As a Leo, I’ve always wanted to feel more connected to the constellation—but I never saw a lion. Stellarium’s version reads mouse to me (not duck), but Rey’s interpretation has always resonated more … probably because I was a horseback rider, and I’ve always thought it looked more like a horse. Seeing that shape made it feel like mine in a way the abstract star blobs never did. I’m intrigued by the idea that these shapes weren’t meant to be literal depictions—that actually explains a lot. I’m not totally sure all the classical connections land for me, but I love the direction your brain is going with it. Definitely one of those posts that gets me thinking about the sky a little differently.