Continued from Unveiling the Renaissance Metaphor

Many books on tarot begin the story with the French occult revival, we began ours in the Italian Renaissance. Many of the works we discussed in part I became lost in the centuries in-between and would not be rediscovered for some time:

*While Johannes of Rheinfelden’s Tracatus survived in 4 different manuscripts, it would not receive much scrutiny until Edward Augustus Bond translated it in 1878 when the British Museum acquired their copy.

* Marziano’s Treatise on the 16 Heroes was first discovered by Paul Durrieu in 1895.

* The Steele Sermon wouldn’t be rediscovered until 1900. Robert Steele was also the first to put forth a theory that Tarot was once called Trionfi.

* Both XVI century essays on tarot would become lost until Franco Pratesi found them again in 1987.

These works are thus unknown to many of the characters that we will meet in this chapter. Continuing our investigation into the meaning of tarot we now move on to Paris shortly before the French Revolution.

Antoine Court de Gébelin (1725 - 1784) is widely credited for popularizing tarot as an esoteric medium. Despite having been an ordained pastor he was much more interested in classical religions and occult philosophy. A social climber, he borrowed his paternal grandmother’s name ,de Gébelin, in an effort to blend in better with aristocratic circles.1 He was involved in different masonic lodges throughout his life including the famous Les Neuf Sœurs (The Nine Sisters) which he shared with Benjamin Franklin and Voltaire. De Gébelin had friends at court and would even be appointed royal censor towards the end of his life.

De Gébelin’s experience with tarot was much like Piscina whom we discussed in Part I. He had first became intrigued by the game while watching some ladies play at a party he was attending. He got so excited by the cards that he disrupted their game, snatched up the trumps, or as the French would say the ‘atouts’, and then began to explain their symbolism on each card. Caught up in the Egyptomania of the day he declared that the cards were a remnant of a secret book that preserved the teachings of the classical Egyptian religion. He would go on to publish his theory in his Monde Primitif, Vol. 8 in 1781.

When De Gébelin spoke of an Egyptian book he was referring to a group of ancient and medieval texts known collectively as the Corpus Hermeticum that claim authorship from the legendary sage Hermes Trismegstus. The works of Hermes were popular during the Italian Renaissance which had experienced its own wave of Egyptomania in the 1420’s following the discovery of the Heiroglyphica of Horapollo. However the Hermetica would not see a translation into Latin until Marsilo Ficino published his in 1471. Prior to Ficino, the only Hermetic work that was available in Latin was the Asclepius.

Reconstructing the hypothetical primeval golden age had been the focus of De Gébelin’s Le Monde Primitif series of encyclopedias. He had theorized that “tarot” meant the “royal road” in Egyptian, of course this was said before Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt when the Rosetta Stone was discovered. Most of De Gébelin’s card interpretations are also through this pseudo-Egyptian lens: the Pope’s triple cross staff is Egyptian, the chariot rider is Osiris, the devil is Typhon, the moon and tower depict Egyptian fables and so on. He famously flipped the Hanged Man over and called it ‘dancing prudence’, though a few other decks had previously done this.

In his ordering, de Gébelin placed the fool last stating:

“As for this Atout, we number it ZERO, though we place it in the game after XXI because he does not count by himself, & only possesses the value that it gives the others, precisely like our zero: showing thus that nothing exists without its folly” 2

If you may recall, the anonymous essay from 1570 made a similar statement about the fool, that same essay also referred to the cards as ‘heiroglyphs’. De Gébelin had an allegory for the suit cards as well that was based on the estates of man: Swords represented the nobility, Clubs the farmers, Cups the clergy, and Coins the merchants.3

Published along with De Gébelin’s article in Le Monde Primitif was an essay by the Comte De Mellet (1727 - 1804) who saw within the septenary structure of the trump cards an allegory for the ages of man. Both de Gébelin and de Mellet thought that the trump sequence should be read backwards as they had believed Egyptians counted backwards thus de Mellet’s interpretation began in the Golden Age with creation. He interpreted the World card to be the cosmic egg that existence was born out of and the Judgment to really be the creation of man. The following age, the silver age, began with the Temperance card and ended with the Hermit seeking Justice. The Last age containing the temporal rulers was the iron age, our present fallen state with the fool card at 0 representing the lowest condition of man. De Gébelin and de Mellet’s backwards interpretation would not see adoption from subsequent gurus.

Jean Baptiste Alliete ‘Eteilla’ (1738 - 1791) is remembered as the first professional fortune teller to read tarot cards and he is credited with inventing card spreads. Prior to Eteilla everyone just drew one card, or so the legend goes. He had learned to read cards as a teenager and it’s possible that he knew a tradition going back to the Italian Renaissance. In his later writings he would claim to have learned his method in Brittany from an elderly gentleman from the Piedmont. Tarot historian Ronald Decker argued in his book that since the Italian roots of tarot were not well known at the time, Eteilla could have simply claimed to have been taught by an Egyptian if he had intended to be deceptive.4

Eteilla had first published a cartomancy book Etteilla, ou Maniere de se recreer avec un jeu de cartes (Etteilla, or (A way to entertain one’s self with a deck of cards) in 1770 teaching a method of card reading that utilized the popular 32 card piquet deck. In 1783 he would publish the first cartomancy guide using tarot cards, Manière de se récréer avec le jeu de cartes nommées tarots (A way to entertain one’s self with the deck of cards called tarots). He had originally submitted the manuscript in 1782 but a royal censor, possibly de Gébelin himself, suppressed it.5 Two years later, in 1785, he would author what is regarded as the last book on classical alchemy with Philosophie des hautes sciences : ou la clef donnée aux enfans de l'art, de la science & de la sagesse.

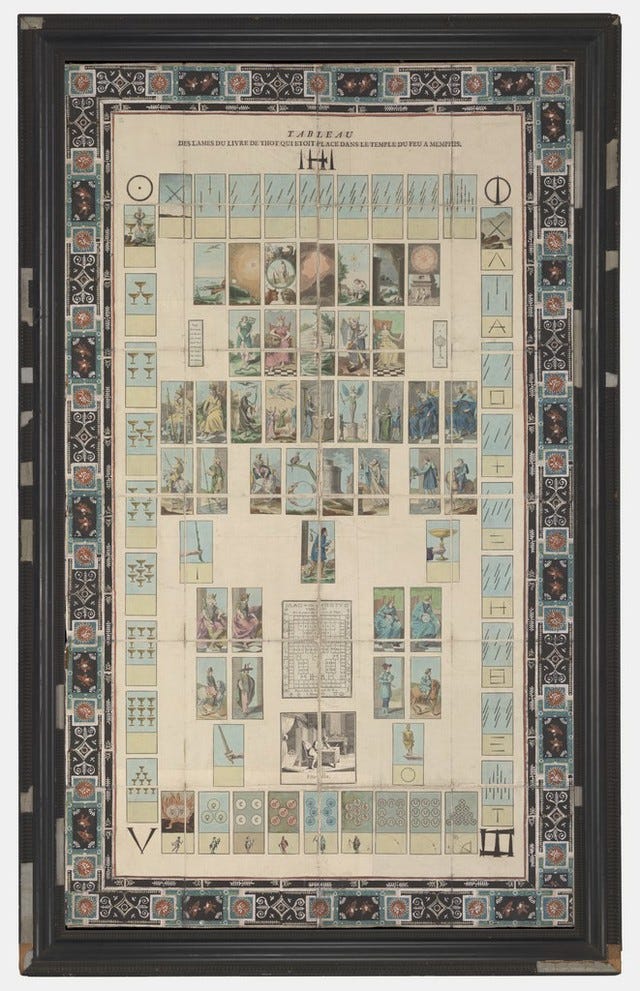

A printer by trade, Eteilla created his own deck, the Livre de Thot, around 1789, and it remains one of the most striking and beautiful tarot decks ever created. Like de Gébelin , he saw the creation story in the tarot sequence and thus based his new deck around the hermetic Poimandres with some principles incorporated from alchemy and astrology. He saw the suit cards as corresponding to one of the 4 classical elements with Swords representing Air, Clubs as earth, Cups as water and Coins as fire. I theorize that the Renaissance Sola Busca deck may have also used these same correspondences.

Whether they admitted it or not, all of the subsequent tarot gurus of the French Occult Revival would adopt some of Eteilla’s ideas, especially his interpretations of the pip cards.

Interest in tarot waned during the first half of the nineteenth century until it was revived by the work of Éliphas Lévi (1810 - 1875). Lévi was a fascinating character and quite talented as he was an accomplished writer, artist and musician. A former priest, Lévi had become interested in tarot and magic later in his life and it was through the synthesis of both that he lit a fire that has managed to stay burning into our present time.

In an effort to not cite Eteilla as a source, Lévi sought to prove that older authors had noticed the occult significance of the figures on the tarot cards. Many of his claims stem from a book simply having 21 or 22 chapters - such references included works by Louis Claude de Saint-Martin, Giarolamo Cardano and even the Book of Revelation. One of the more interesting early allusions he noted was a key diagram (see above) that he falsely attributed to Guillaume Postel in his 1547 Absconditorum Clavis. This diagram included a circle with the letters TARO arranged at it’s cardinal points which could be read as ROTA (Latin for Wheel) or TARO (You Guessed it- Tarot) and later on also added ATOR (Hathor) and TORA (Torah).6

Lévi rearranged Eteilla’s elemental correspondences to be in keeping with other esoteric traditions . Now the Clubs were magic Wands spewing forth fire and the Coins were made earthly and material. These correspondences would see later adoption from the Golden Dawn and seems to be the one most commonly referenced in modern Tarot.

The Comte de Mellet had been the first to suggest a connection between the 22 cards of the trump sequence, Éliphas Lévi would greatly expand on this. In his earlier works Levi had based his correspondences on Athanasius Kircher’s system. With his 1861 book La clef des grands mystères (The Key to the Great Mysteries) he would change over to a system based on the foundational Kabbalistic work, the Sefer Yetzirah (The Book of Formation), thus connecting tarot once again to an account of creation. As this teaching goes, the Abrahamic God, YHVH, spoke the world into existence and each letter of the Hebrew alphabet represents a different step in this process. Following this order, correspondences are made between the major arcana and the planets, the elements and the Sephiroth of the Kabballah.

A major problem with Lévi’s hypothesis is that Kabbalistic thought was relatively unknown in Christian Europe until the humanist writer Pico della Mirandola published a Latin translation of the Hebrew esoterica in 1486 - several decades after the first tarot decks had been created. A further difficulty emerges when attempting to tie Pico to tarot as he possessed a strong aversion to games of chance and viewed fortune-telling as contrary to the concept of free will.

This is not to rule out that sometime after Pico a secret Kabbalist tradition may have arisen within the tarot community. For instance many parallels have been noted between Eteilla’s pip interpretations and the writings of the 13th century Kabbalist Joseph Gikatilla’s Sha'are Orah (Gates of Light) possibly indicating an indirect influence.7 While there are some Kabbalist interpretations of the tarot cards that make so much sense they seem intentional, the aforementioned circumstances suggest such features were unlikely to have been part of the game's original design.

Following Lévi , there are a few other important gurus such as Paul Christian, Oswald Wirth and Papus. Each of these men had some contributions in their own right however none of them moved the conversation beyond the Egyptian origins/ Hebrew alphabet paradigm.

Also in the late 19th century emerged the Victorian occultists the Golden Dawn lead in part by S.L. MacGregor Mathers . Tarot had never really seen adoption as a game in the English speaking world, and thus from its introduction, it has always been seen in those countries through an occult lens. The Golden Dawn would further refine the tarot correspondences of Eteilla and Levi into a system blending numerous esoteric traditions that remains popular today . To fit in with this new system the Strength and Justice card’s placement within the Tarot de Marseille were swapped to better correspond with the Zodiac - the later Rider-Waite Smith Deck’s ordering retains this same concept.

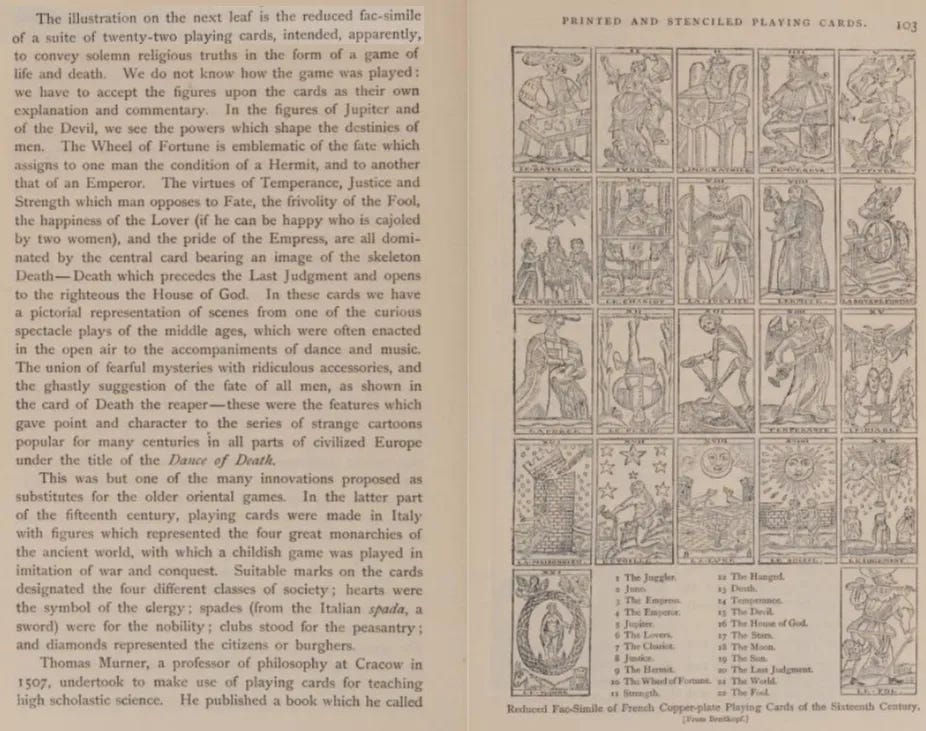

Although the medieval Italian origins of tarot cards were not well known during this period, they were not forgotten entirely, there were some writers that took a more historical approach to the subject. W.A. Chatto, in 1848, published the first history of playing cards in which he proposed a Chinese origin for card games.8 In 1784, just three years after de Gébelin’s essay, Johann G.I. Breitkopf wrote Versuch, den Ursprung der Spielkarten in which he proposed a relationship between the trump cycle and the Dance of Death, . Later authors such as Gabriel Peignot, Paul Lacroix, Schultz Jacobi, Georges Kastner, and Theodore Low De Vinne (see above) would follow suit and propose similar theories, which may or may not have been informed by Breitkopf.9 The Dance of Death was a popular motif that emerged following the black plague in the middle ages and remained a cultural phenomena well into the 19th century. Indeed the broader lesson that death comes to everyone regardless of station or status is reflected overtly on the Tarot de Marseilles XIII card itself where an allegory of death personified can be seen reaping a field sowed with kings, bishops and popes alike.

In the next installment our investigation continues as we look into theories on tarot’s meaning from the 20th century and beyond, I hope to see you all there in:

PART III : HUNTING THE UNICORN

Michael Dummett, Ronald Decker & Thierry Depaulis

A Wicked Pack of Cards - The Origins of the Occult Tarot (1996) [Pg. 52-53]

Antoine Court de Gébelin with Comte de Mellet

The Game of Tarots/Research on the Tarot, Le Monde Primitif, Vol. 8 (1781)

[Begins on pg. 365] Archive Translation

Stuart Kaplan,

Taro Classico (1972) [Pg. 40]

Ronald Decker,

The Esoteric Tarot: Ancient Sources Rediscovered in Hermeticism and Cabala (2013) [Pg. 190] *page number from ebook

Ibid., [Pg. 189*]

Michael Dummett, Ronald Decker & Thierry Depaulis

A Wicked Pack of Cards - The Origins of the Occult Tarot (1996) [Pg. 173-174]

Decker (2013) [Pg. 221*]

William Andrew Chatto,

Facts and speculations on the origin and history of playing cards (1848) Archive

Michael Hurst,

pre-gebelin.blogspot (January 2009)

Fascinating article, thank you!!!