Continued from Occultation

In part I we reviewed the scant editorial evidence on the meaning of tarot that comes down to us from the renaissance. In part II we sifted through the teachings of the French school during the Enlightenment. In this installment we will be surveying the early modern studies into tarot iconography.

Arthur Edward Waite (1847 – 1942) was a Christian mystic and scholar, a prolific author and translator, a member of various occult societies throughout his life including the Golden Dawn and as the co-creator of the famous Rider-Waite Smith Tarot (1909) he is easily one of the most recognizable figures in all of tarot. Waite represents a bit of a reform character in the history of tarot as he dissented from many of the ideas of the French School such as de Gébelin’s hypothesis of an Egyptian origin and Lévi’s system of Hebrew Alphabet correspondences. Waite did however seem to favor the 3-part structure for the trump sequence originally suggested by the Comte de Mellet. In his famous 1911 The Pictorial Key to the Tarot, following his descriptions of what he called the ‘Trumps Major’ Waite vaguely alluded to the ‘three worlds’:

“There has been no attempt in the previous tabulation to present the symbolism in what is called the three worlds—that of Divinity, of the Macrocosm and the Microcosm. A large volume would be required for developments of this kind. I have taken the cards on the high plane of their more direct significance to man, who—in material life—is on the quest of eternal things. The compiler of the Manual of Cartomancy has treated them under three headings: the World of Human Prudence, which does not differ from divination on its more serious side; the World of Conformity, being the life of religious devotion; and the World of Attainment, which is that of “the soul’s progress towards the term of its research.” He gives also a triple process of consultation, according to these divisions, to which the reader is referred. I have no such process to offer, as I think that more may be gained by individual reflection on each of the Trumps Major.”1

Perhaps we can account his reluctance in 1911 to one of his oaths of secrecy as he obviously knew much more at that time than what was revealed in that short book. Many years later in his 1926 article The Great Symbols of the Tarot, Waite was a bit more elucidating:

“I satisfied myself some years ago, and do not stand alone, the Trumps Major existed originally independently of the other arcana and that they were combined for gambling purposes at a date which it is possible to fix roughly. I am concerned only on the present occasion with what may be called the Great Symbols. They are twenty-two in number, and there is no doubt that some of them correspond to estates and types.”

“I have spoken of classification under types, estates or classes, but it obtains only in respect of a few designs, seeing that the majority of the Trumps Major are occasionally allegorical and in several cases can be understood only as belonging to a world of symbols, while a few are doctrinal in character - in the sense of crude Christian doctrine. The Resurrection card and the Devil belong to this last class. Death, on the other hand, is a very simple allegorical picture-emblem, like the Lovers, Justice and Strength. The symbolical cards, which must be so termed because certainly they do not correspond to the admitted notions of allegory, are the Hanged Man, Chariot, the so-called card of Temperance, the Tower, the Star, the Sun and Moon, and that which passes under several names, one of which is the World. The Wheel of Fortune is seemingly of composite character, partaking of both allegory and symbolism, while the Fool is very difficult to class. On the surface he may be referable to that estate which inhabits the lowlife deeps - the mendicant and vagabond type.”2

He saw a grouping within the lowest and the highest trumps but couldn’t make good sense of the middle. Unfortunately the above quoted is about as deep as this article went as Waite spent the majority of it rehashing his debates with the French.

William Marston Seabury (1878 – 1949) was a lawyer for the film industry and an avid bridge player. He had many theories regarding the tarot pack but unfortunately died before he could really flesh any of them out. His wife had some his notes privately published for friends after his death in 1951 as The Tarot Cards and Dante’s Divine Comedy. The result was a 28 page treatise, a pioneering work in the history of playing cards as it was one of the first to have placed tarot within it’s proper medieval context. Due to its tiny print run, this is a very rare book that only a handful of libraries have on hand in the present day.

In the book’s preface, taken from his writings before he died, Seabury explained that he had observed many of the same characters and subjects from the tarot pack while reading the works of Divine Comedy of Dante. He became even more convinced of a connection after reading Dante’s other works including Vita Nuova, his Il Convito and his De Monarchia. This lead him to search for tarot cognates across the corpus of medieval literature of which he cites Boccaccio’s de Casibus and the works of Giotto as notable examples.

With the preface being the only part of the book that was somewhat complete the remainder is mostly a collection of notes with a dash of theorycraft here and there. Throughout the text we are treated to a scattershot of possible leads where he begins by searching for a connection in other games:

“First on the list is the simple, unobtrusive little Die.

The origins of dice are beyond the period of factual history, but not beyond traditional and familiar mythology. Homer is said to have written his Odyssey about 850 B.C. He wrote of much earlier times, yet his famous Ulysses is said to have played the game of Goose with dice, under the shadows of the Walls of Troy.

Now, these apparently innocuous and meaningless little cubes we know as dice are probably the most heavily concentrated mites of symbolism ever devised by the fertile mind of man.

Everyone knows that a Die is a cube having numbers from 1 to 6 inclusive on its sides. Doubtless many have observed that the dots are so arranged that the 1 is always opposite the 6, the 2 opposite the 5 and the 3 opposite the 4, so that these opposites always add up to the number 7 while the numbers run only from 1 to 6 inclusive.

So much is within the ordinary powers of untutored observation, but what many may not know is that at least from the days of Pythagoras (c. 582 B.C.) the digits from 1 to 9 acquired a significance from which may be extracted the substance of the story of the Creation as understood centuries before the Christian Era.”3

His notes move on from games and into a discussion of the Florentine Guilds mostly sourced from Machiavelli’s History of Florence. He tries to relate the number of guilds, there were -at one time - 21 lesser guilds, to the structure of the tarot pack. He also proposed a similar relationship between the 4 divisions of the city and the 4 card suits. No deeper meaning is suggested beyond surface level numerical coincidences

In the next section we find Seabury’s notes on Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375). Boccaccio seems to meet much of the general criteria put forth so far as he was an influential medieval literary figure who also had a relationship with the city of Florence. The poet’s father was from Florence, he was known to have lived there at one point and he had even authored a biography on Dante.

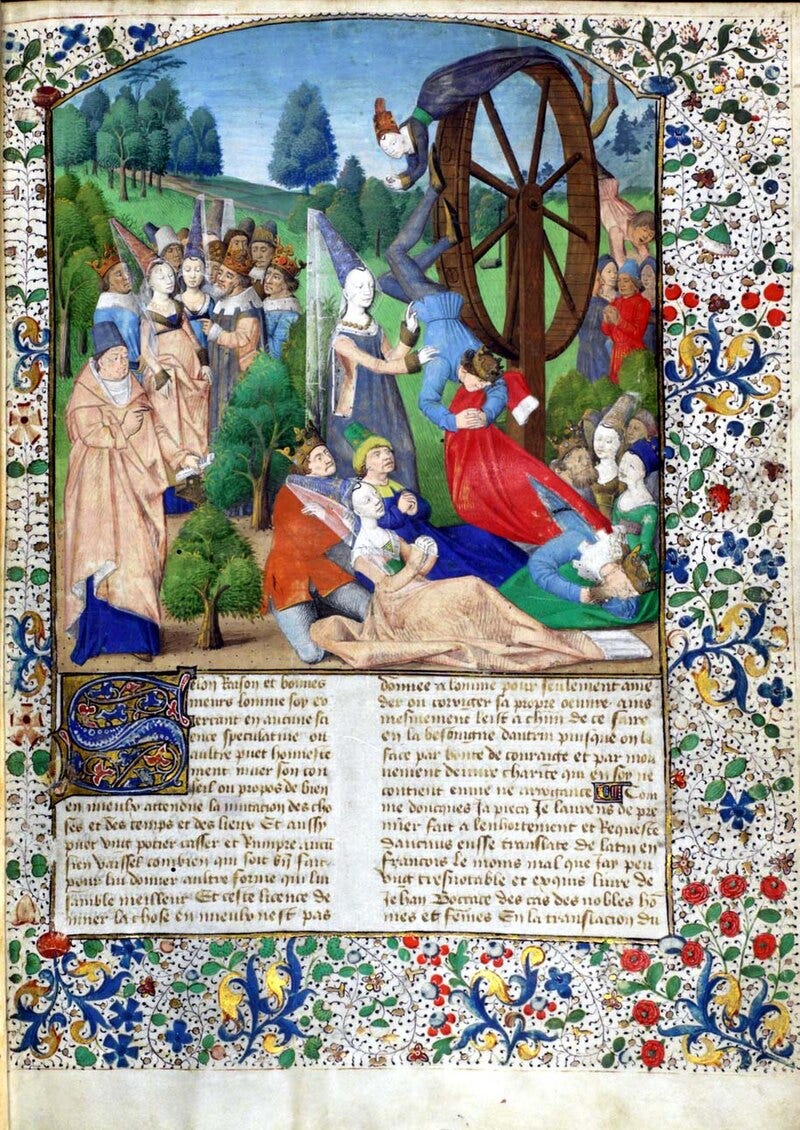

Most notable are Seabury’s observations on De Casibus virorum illustrium (On the Fates of Famous Men):

“It has been suggested that Boccaccio’s work might well be described as a History of Fortune, for it is a collection gathered throughout the centuries, which describe the most memorable and crushing blows that befell the illustrious personages of mythology and history, written, as the author himself declared, with the object of teaching princes the virtues of wisdom and moderation by holding up to their view examples of misfortune provoked largely by their own egotism, pride and vaulting ambition. This sounds much like one of Dante’s objectives.”4

De Casibus is indeed rife with imagery of the rise and fall and the fates of men that seems to fit well with the art direction of the 2nd act of the trump sequence. Seabury manages to tie in a great number of subjects found in De Casibus to figures from the tarot pack such as the Creation Myth (Love), Nimrod (The Tower) and Hercules (Strength). He even tries to tie Boccaccio’s 4 Kings of the Lombards to the 4 Kings of the Suit Cards.

Seabury had noted that he had read Lydgate’s translation of De Casibus. John Lydgate (1370-1451) an English poet and Benedictine Monk had based his translation of a French edition of De Casibus which included a section on the infamous Pope Joan that had been taken from Boccaccio’s De Mulieribus Claris (Concerning Famous Women). Pope Joan was a medieval fable dating back to 855 about a woman who, posing as a man named John, successfully infiltrated the Church hierarchy working her way up until she became the duly elected pope. Her true identity was not discovered until she had given birth at St. Lateran and thus the legendary scandal ensued.

Next comes a discussion of holiday festivities:

“This review would not be complete without a reference to the Feast of Fools, because that ancient institution shows the immense popular predilection for amusements, satires and ribaldry and even gross burlesques of the Catholic Faith, the Church and all of the Clergy from Pope to Deacon. As its name implies, the emphasis placed upon Fools and foolery was not intended to refer to any personal or malignant type, but more particularly to depict Fools in general, as a travesty upon the greatest institution of all times after the beginning of the Christian era.”5

Following this introduction, Seabury presents a theory that connects the 4 card suits to the 4 classes of society. This interpretation, which had already been suggested by de Gébelin, relates the clubs to the peasants, the clergy to the cups, the swords to the nobility and the coins to the merchants. The notes continue, pondering the Feast of Fools from it’s roots in the Ancient Saturnalia up until episodes in the Renaissance.

From the Feast of Fools we segue into another performance tradition, The Dance of Death. Also discussed in passing was Ship of Fools (1494) whose allegorical similarities had likely been informed by both traditions. As in De Casibus and Dante, Seabury observed a wealth of tarot cognates within the Dance:

“Marginal notes in Prayer Books said to have appeared in Paris in 1495 describe two Dances of Death. In the first, the Danse Macabre depicts the Pope, the Emperor, the King, the Chevalier and a long list of some twenty-seven men and about the same number of women. Many of these familiar figures are to be found in the Tarot pack.

The second dance presents over fifty subjects or characters which include the following, every one of which is also depicted as a specific card by the earlier Tarots: 1. Death, described as the Triumph of Death which may have been derived from Petrarch’s Triumphs of Death; 2. the Pope; 3. the Hermit; 4. the Emperor; 5. the Empress; 6. the King; 7. the Queen; 8. the Knight; 9. the Lovers; 10. the Beggar, sometimes combined in the Tarots with the Fool; 11. the Last Judgment. Others describe the Creation, the Fall, the Expulsion from Paradise, the Punishment of Man, the Certainty of Death, the Uncertainty of Death, Christ’s Victory, Salvation, and True and False Religions, all embraced within the interpretation of the Tarots here presented.”6

The book wraps up with a section on Dante that consists of mostly biographical information. With the bulk of Dante theorycraft having occurred back in the preface, the closest thing we get in this part is a brief back and forth about the pope and emperor within a discussion of De Monarchia. Like Mr. Waite and the Comte de Mellet before him, Seabury recognized the three distinct subject matters represented within the tarot trumps:

“As [Dante] regarded life to be of three sorts, the vicious life, the advance toward virtue and the virtuous life, he divided his work and treated his subject in three parts, the first in which condemned the wicked and in the last rewarded the good.”7

On the final page we are left with just an outline of the Dante theory and can only speculate as to what Seabury had meant by it.

While the 3 part structure fits well between the tarot pack and The Divine Comedy a few cards in particular really do have to move to get the analogy to work. The Devil needs to be there at the end of Part 1. The lower trumps could have remained in this part, at least the Pope and Emperor, as the Guelph-Ghibelline rivalry played a major role throughout the Inferno. I would have also expected to have found Fortune down there as well to represent Virgil’s sermon in canto VII.

The Chariot certainly needed to be moved to correspond with the scene with Beatrice at the end of Purgatory. Among the artwork chosen for this book were drawing by Botticelli and a selection of cards from the Pierpont-Morgan collection. Perhaps from this we can infer that Seabury had interpreted Bembo’s Chariot as Beatrice?

Whatever the case may be, as Seabury’s Dante theory only works if the trump cards were to be rearranged into an exotic new order never before attested the works of Dante were therefore likely not the basis for narrative structure of the sequence.

Next on our list is Gertrude Moakley (1905–1998), who authored the first scholarly study on tarot iconography. Moakley has already been honored on this blog with a full-length article detailing her theories, which you should read if you haven’t already, before moving on to the next segment as her work is important foundational material that will be referenced later. You can check out the Moakley article here:

Gertrude Moakley & The Triumphs of Petrarch

Our investigation will pick up again after Moakley in ‘ Hunting the Unicorn II’, An Investigation into the Meaning of Tarot, Part 3.2 - I hope to see you all there!

William Marston Seabury,

The Tarot Cards and Dante’s Divine Inferno (1951), Tarot History Forum

Ibid.,

Ibid.,

Ibid.,

Ibid., [Pg. 24]

This is fascinating! Thanks for sharing all of this with us... I love it 🤍