Hunting the Unicorn II

Tarot secrets revealed! Surveying works from Paul Huson, Joseph Campbell and Michael Dummett

An Investigation into the Meaning of Tarot - Chapter 3, Part II

Continued from Hunting the Unicorn & Gertrude Moakley & The Triumphs of Petrarch

In this series we have been looking at the various theories that have attempted to explain what the underlying metaphor behind the tarot deck may have been. So far most of these theories have amounted to no more than noting cognates, essentially recognizing the broader symbolic vocabulary that influenced not only tarot but the broader corpus of medieval art and literature. Thus far we have entertained the following suggestions:

The Danse Macabre suggested by Breitkopf, Low De Vinne et. al.

Dante’s Divine Comedy, as well as his other works, Boccaccio’s De Casibus and everything else that was in Seabury’s notes, which also included the Danse Macabre.

The Triumphs of Petrarch suggested by Gertrude Moakley.

Seabury and Moakley both entertained a connection to dice games with Moakley discerning the significance of 21 and 56 as the outcomes of dice rolls. As their books are quite rare, Moakley’s having only seen one printing and Seabury’s a limited private label, both authors would largely go unnoticed by the tarot community until the age of the internet.

1971 - Paul Huson, The Devil’s Picturebook

Paul Huson (1942- ) is an author famous for his many books on witchcraft and esotericism. In the 1960’s he was involved with Dion Fortune’s Society of the Inner Light and had studied the Golden Dawn’s method of ceremonial magic under Israel Regardie. In 1971 he would publish a study on tarot symbolism with The Devil’s Picturebook which was quite popular in its’ time. This is a pretty solid beginner’s tarot book, in the first chapter Huson teaches how to both do readings and play games with the cards. Next comes a survey of ‘the little there is of documented tarot history’. The typical occultist claims are discussed: Egypt, gypsies etc. but he ultimately settles on tarot being a memory game used to preserve pagan and gnostic teachings:

“The occult principle behind a deck of tarot cards may also owe a lot to monasticism, if not for originating it, then at least for preserving it. Memory served far a greater purpose for the medieval monk than it does for us nowadays. All books then consisted of laboriously hand-written manuscripts. Indeed, the art of writing itself was hard to acquire. In view of this, vast tracts were often committed to memory. Memory or "mnemonic" systems similar to those so widely advertised today were very much in demand.

The most simple type of mnemonic system consists of a series of pictorial images, usually arranged in some special order, which may be used as a mental filing index or pigeonhole rack. The medieval student monk could, by vividly visualizing each portion of the tract he wished to learn, file the section away in one of his memory boxes until he needed to take the tract out of mental storage and look at it again. All that would be needed then was a return to the correct category image in order to release the associated portions. A similar type of memory system, using plants and trees and the digits of the hand as category images seems to have been used by druids and bards long before their Christian successors, the Dominican and Franciscan monks.” [Pg. 62-63]

While Huson doesn’t elaborate much past what was quoted here, recognizing medieval mnemonic notation techniques goes far to explain many of the quirks found in the art of the Tarot de Marseille.

The picture above is from a 16th century book full of mnemonic charts, in this chart we see a selection in items in three rows, each item is related in some way to the other objects in the same vertical row though some are more apparent than others. An image of a hand was often used to indicate 5’s as well as numbers ending in 5 and a cross or an ‘x’ denotes multiples of 10s. In the tarot deck note how 5. The Pope is raising a hand as well as 15. The Devil, a cross appears in the design of 10. The Wheel as well as on the flag of the angel of 20. Judgement and let’s not forget the lemniscate hat of 1. The Juggler and 11. Fortitude. Huson is correct that the use of mnemonic images is ancient as we have examples going back to Roman times such the ad Herrenium.1

The following chapter, ‘Tarot Sorcery’, gives a brief history of western esotericism which is far better than this book’s survey of tarot history. Here Huson talks about cool stuff such as grimoires, The Goetia, Gnosticism, Giordano Bruno and the Golden Dawn. The next chapter , ‘The Old Religion’, provides a short survey of pagan beliefs and customs. The rest of the book is dedicated to interpretations of each of the major arcana.

The central idea of this book is that the tarot memory game was preserving is a story of the life of Dionysus. Huson connects The Fool to Dionysus citing the asshat he is shown wearing on some of the XV century tarots, The Magician, also, is cast largely by virtue of his hat, the petaso. While this is a common interpretation, with the Fool as Dionysus we had an opportunity for a Nietzschean showdown - after all Waite said The Magician was Apollo. The Empress and Emperor are Dionysus’s earthly mother and father, The Pope and Popess are his spiritual parents. The Chariot is Mars etc. Huson’s interpretations are largely in line with the Golden Dawn correspondences.

I probably found his interpretation for The Hanged Man to be the most interesting:

“Dionysus, the ass-eared Fool, has reached the end of his Saturnalia. His time has elapsed. He must perish in order to be reborn as Iacchus, even as the seed must descend into the earth to grow again the next year.

In Greece, images of Dionysus were frequently hung in trees as a means of securing fertility for the vines and crops. This ancient belief persisted in Europe under the guise of such practices as stoning an effigy at Lent known as a Jack o' Lent. "Jack" may possibly be derived from "Iacchus" or "Jacco." After the effigy had been taunted and abused, simulating the Titans' treatment of Dionysus, it was frequently burned, shot at or simply thrown down a chimney. The Saxons, however, continued to hang it from a tree.

Though he was known as Jack o'Lent, some thought the effigy to be that of Judas Iscariot. Actually it symbolized the entire spirit of the winter carnival over which the Lord of Misrule had presided. The bound, hanging figure shown in the Hanged Man is undoubtedly this Judas Iscariot. The coins sometimes shown pouring from the twin pouches he clutches in either hand are the thirty pieces of silver for which he sold Jesus to the Romans. He has been "baffled"—hung by his heels, the ancient punishment inflicted upon debtors. But lurking behind this orthodox image is that of Jack o'Lent, and behind that is Dionysus embarking upon his descent into the underworld.

The myth of the dying god is a shamanic one, as we have already seen. The Hanged Man shows us the death itself.” [Pg. 200-201]

In the above passage Huson tied in The Hanged Man with an old timely English tradition, ‘The Jack o’ Lent’ which sounds very similar to the tradition Moakley cited from The Golden Bough to explain the crown of feathers Bembo’s Fool is wearing.

Along with some of his card interpretations, Huson provides instructions on how to perform a magic spell related to the card. The spell that he provides for The Fool is supposed to make you invisible, which is always a fun trick. For The Magician he teaches us how to perform elemental augury. For The Chariot, a talismanic revenge spell taken ‘from Florentine witchlore’.

A major problem with the Dionysus theory is that putting the classical gods on cards wasn’t something people in the Renaissance needed to be shy about. There exist many examples where we find the gods depicted on cards such as the pre-tarot Marziano deck, the Sforza Castle Well Cards, the Viti-Boiardo deck, The Leber Rouen and so on. In some municipalities Jupiter and Juno were deemed a more acceptable alternative to the Pope and Popess. That aside I do think Huson was on to something, maybe not Dionysus himself but Dionysion elements are arguably present in the tarot iconography.

I do find it a bit perplexing that Huson would have a Fool is Dionysus theory and not mention the constellation Orion. There seems to have been a tradition in tarot to paint The Fool in an ‘Orion Pose’. The constellation is related to a host of dying and rising gods, but most importantly Osiris - who was syncretized with Dionysus. While I have found numerous blogs and forum posts discussing this connection, I am yet to read a book that mentions it. Figuring out the meaning behind this tradition was my first big question in tarot and for a fleeting moment I thought I might have finally found a book that addressed this.

More recently Michael S. Howard has blogged extensively about his own Dionysus theories2 and from what I have read, he doesn’t talk about Orion either. Although, through this experience I may have finally realized a satisfying answer to my question, look for a full article on it soon! (#GetHype)

Huson would publish another tarot book nearly 30 years later in 2004 with Mystical Origins of the Tarot: From Ancient Roots to Modern Usage., which I haven’t read as of writing this but I will before this project is over. I hear good things about this book, it’s supposed to be one of the best.

1979 - Joseph Campbell & Richard Roberts, Tarot Revelations (1979), Archive

When I first heard that the popular mythologist Joseph Campbell (1904-1987) had written a book on tarot I expected to find something similar to his popular hero’s journey motif that we have seen applied to the tarot so many times as ‘the fool’s journey’. Instead, what we got in Tarot Revelations was a short essay by Campbell where he proposed a vague theory that connected the iconography of Tarot de Marseilles to the works of Dante with the majority of the book consisting of Richard Robert’s Jungian interpretation of the Rider-Waite Smith Tarot. Campbell outlined his theory in the book’s introduction as follows:

“for what in the Tarot de Marseilles had most excited by imagination had been its reflection of what I thought I recognized as a tradition expounded by Dante in his Convito. In fact it had been my recollection specifically of Chapters 23 and 28 of “The Fourth Treatise” of that philosophical work that first opened to me, that evening in Big Sur, the message of the four TDM atouts, 6 to 9. Whereupon the sequence of cards 14 to 17 appeared to me to match the order of the poet’s four major works, La Vita Nuova, Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso. ” [Pg. 4]

In contrast to W.M. Seabury who rearranged the tarot trumps to fit the narrative of The Divine Comedy, Campbell cherry picks from Dante’s broader catalog to find the tarot cards. Campbell had likely never heard of Seabury, as it was clear early on that Campbell had done but cursory research into tarot before he began to type his explanations and we were essentially getting a cold take vis-à-vis Court de Gébelin. There is no overall pattern to the atouts themselves with Campbell instead relying an a spread he had devised based around an allegory of the stages of life to provide an explanation.

“Twenty numbered picture cards follow, which have been arranged here in 5 ascending rows of 4 cards each to ‘suggest the graded stages of an ideal life, lived virtuously according to the knightly codes of the Middle Ages.” [Pg.11]

For some of the atouts the only discussion Campbell gives is in relation to it’s location in this spread, which felt lazy. Still he was Joseph F. Campbell and his knowledge of folklore and traditions was considerable- he’s going to get a few things right. For instance he interprets the Chariot as Plato’s Phaedrus, something tarot experts such as Ronald Decker and Robert Place would later agree on. The Chariot itself is a very crucial plotpoint from The Divine Comedy showing up at the end of Purgatorio. What’s interesting about this is that he doesn’t mention Bembo’s Chariot which is arguably Dante inspired, Seabury seemed to think so at least. Campbell also doesn’t make mention of Botticelli’s Chariot, which I find to be some of the more compelling reasons to have even done a Dante theory to begin with. Oh what this could have been but unfortunately wasn’t.

1980 - Michael Dummett with Sylvia Mann,

The Game of Tarot: From Ferrara to Salt Lake City

Archive - Chapter 20 only

Sir Michael Dummett (1925-2011) was an Oxford philosopher who wrote extensively on Frege, metaphysics and Tarot. In 1980 he wrote The Game of Tarot with help from playing card aficionado Sylvia Mann thus finally giving playing cards an authoritative history similar to what the great H.J.R. Murray had done for the chess game. This book went far to firmly establish the Italian origins of tarot as attested by the physical and literary evidence and thus Dummett and Mann effectively established the discipline of tarot history.

Dummett plainly stated in The Game of Tarot that he did not think the trump sequence held any special symbolic meaning. The images on the cards were completely standard in medieval and renaissance art and likewise did not require a special hypothesis to explain. From his perspective, there was very little, if anything, that the trump cycle itself could tell us about the tarot inventor’s intentions.

“We shall gain no enlightenment if we study iconography of the Tarot pack. …it is highly improbable that, by this means, we shall learn anything relevant to the game played with Tarot cards, or, therefore to the primary purpose for which the pack was originally devised.” [Pg. 164]

“We can derive some entertainment from asking why that particular selection was made, and whether there is any symbolic meaning to the order in which they were placed; and we may or may not come up with a plausible or illuminating answer. (If we do not, that may not indicate that we have failed to solve the riddle; there may be no riddle to solve.)” [Pg. 165]

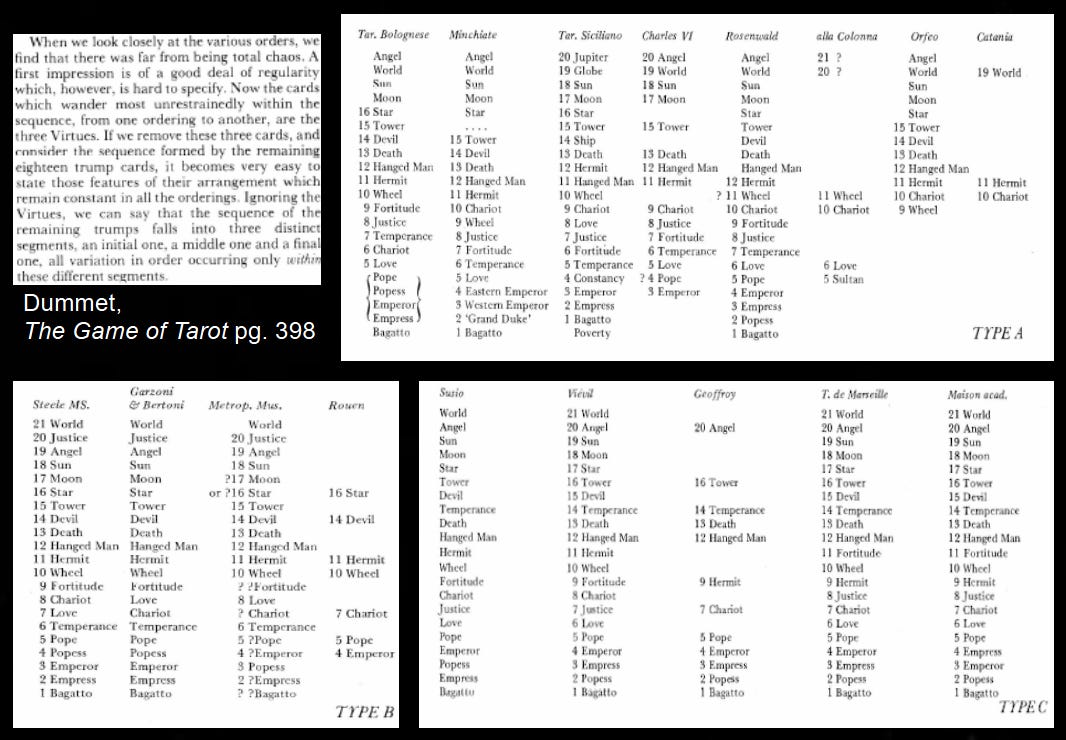

In Chapter 20, The Order of the Tarot Trumps, Dummett explained his views on tarot symbolism which have been referred to as the ‘null hypothesis’.3

“Not all those who have sought to decode the symbolism of the Tarot pack have been occultists; some have been serious scholars, well versed in the iconography of later mediaeval and early Renaissance art. One W.M. Seabury wrote a book to prove that the symbolism of the pack was based upon Dante; Miss Gertrude Moakley, in her fine book about the Visconti-Sforza pack, advanced an interpretation of the pack, supported by much evidence from Italian art and literature; Mr. Ronald Decker has engaged in complicated speculations, linking the pack to the astrology of the time. I am not going to advance another such theory. I do not even want to take a stand about the theories that have been advanced. The question is whether a theory is needed at all. I do not mean to deny that some of the subjects, or some of the details of their conventional representation, may have had a symbolic significance obvious to fifteenth-century Italians, or, at least, to educated ones, that escapes us and may be revealed by patient research; that is very likely to be the case. But the question is whether the sequence as a sequence has any special symbolic meaning. I am inclined to think that it did not: to think, that is, that those who originally designed the Tarot pack were doing the equivalent, for their day, of those who later selected a sequence of animal pictures to adorn the trump cards of the new French-suited pack. They wanted to design a new kind of pack with an additional set of twenty-one picture cards that would play a special, indeed a quite new, role in the game; so they selected for those cards a number of subjects, most of them entirely familiar, that would naturally come to the mind of someone at a fifteenth-century Italian court. It is rather a random selection: we might have expected all seven principal virtues, rather than just the three we find—and, of course, we do find all seven in the Minchiate pack, and they were probably present also in the Visconti di Modrone pack. With the Sun and Moon we might have expected the other five planets, instead of just a star; with the Pope and the Emperor, we might have expected other ranks and degrees. But of course, in a pack of cards what is essential is that each card may be instantly identified; so one does not want a large number of rather similar figures, especially before it occurred to anyone to put numerals on the trump cards for ease of identification. Certainly most of the subjects on the Tarot trumps are completely standard ones in mediaeval and Renaissance art; there seems no need of any special hypothesis to explain them. Whatever may be the truth about those who first designed the Tarot pack, the inventors of the Minchiate pack surely approached their task in the spirit I have suggested: they wanted twenty additional subjects, and they choose ones which it was natural for men of the sixteenth century to think of—the four elements, the remaining virtues, the signs of the Zodiac—and inserted them en bloc in a convenient place. I do not think that anyone has suggested that there is any hidden significance in the sequence of Minchiate Trumps.

That is my opinion; but I do not want to insist on it. It may be that those who first devised the Tarot pack had a special purpose in mind in selecting those particular subjects and in arranging them in the order that they did: perhaps they then spelled out, to those capable of reading them, some satirical or symbolic message. If so, it is apparent that, at least by the sixteenth century, the capacity to read this message had been lost. There are many references to tarocchi in sixteenth-century Italian literature, in which their symbolic potentialities were exploited, but always in an obvious way: no hint survives that any more arcane meaning was associated with them." [Pg. 387-88]

Dummett cited some familiar names there in the beginning then proceeded to make some important points. Whether or not a game needs to have a symbolic meaning is important to consider. Most of the subjects in tarot are indeed standard in medieval and Renaissance art with The Hanged Man being the sole exception. This concept of no underlying symbolism, just common images without a cohesive narrative in mind has been referred to as ‘the triumphal sampler’.4 Dummett closes his monster paragraph with a point about Minchiate similar to the argument I was making earlier in the essay in regards to Huson’s Dionysus theory.

After a brief discussion of Lollio and the lost meaning of tarot in the 16th century (See Part 1), Dummett gives us an important lead in solving the tarot riddle:

“The search for a hidden meaning may be a unicorn hunt; but if there is a meaning to be found, only a correct basis of fact will lead us to it. The hidden meaning, if any, lies in the sequential arrangement of the trump cards; and therefore, if it is to be uncovered, we must know what, originally, that arrangement was.” [Pg. 388]

By narrowing down the various card orders running around in the XV century down to 3 basic types Dummett laid the foundations to actual solving tarot’s riddle. Though he was wrong that we need to know what the original ordering was to interpret the intended metaphor, it can be argued that he even contradicted himself as he claimed it was the subjects on the cards were random selection then went on to prove they were anything but. Dummett found that if he ignored the placement of the virtues the remaining 18 cards were fairly consistent between orderings and fell into three segments with subjects representing distinct themes and any variation occurred only within each segment. That is to say, for instance, you never see a temporal ruler occurring after the Lovers nor do you ever see one of the astrology cards (The Sun, The Moon, etc) appearing before The Tower .

Dummett would expand on this idea in his 1985 article Tarot Triumphant: Tracing the Tarot [Tarot History Forum]

“The individual subjects used for the trionfi appear to have been standardized early in the history of the pack: with few exceptions. all fifteenth-century packs use the same set of subjects. The matto is not, strictly speaking. one of the trionfi —although it is a mistake to suppose any historical connection between it and the joker, which originated in nineteenth-century America. The remaining twenty-one cards may he divided into three groups. The lowest is the bagatto, almost always called bagatella in the fifteenth and sixteenth, centuries; the name is probably an indication of the low ranking of the card rather than a reference to its subject. A merchant or mountebank is shown seated at a table spread with his wares; in some versions customers are gathered around. The occultists' idea that he is a magician is without foundation, as is the notion that the four suit symbols are to be seen on the card. The next four are the papal and imperial cards (called papi in Bologna): the pope. the emperor, the empress. and the papessa. Occultists call the pope and papessa the hierophant and the high priestess. but the figures in the traditional pack had unquestionably Christian characteristics: however, in many later packs these Christian characters were replaced by other figures. The papessa must have been included in a ribald spirit. The earliest surviving example of this card is from the pack painted by Bonifacio Bembo for Francesco Sforza, duke of Milan. soon after 1450. Gertrude Moakley. in The Tarot Cards Painted by Bonifacio Bembo for the Visconti-Sforza Family (New York. 1966), has pointed out that it represents Sister Manfredi, a relative of the Visconti family who had been elected pope by the heretical sect to which she belonged, and had been burned at the stake in 1300. Possibly this was the first time the papessa appeared in the tarot pack: it may have replaced the missing cardinal virtue of Prudence.

The next group of cards could be described as representing conditions of human life: love, the cardinal virtues Temperance and Fortitude (always referred to in early sources as la Fortezza, not. as she is now. la forza) and Justice: the triumphal car; the wheel of fortune: the card now known as the hermit: the hanged man: and death. The wheel of fortune was a well-known symbolic theme of medieval and early Renaissance Europe The animals now found on the wheel of some modern cards are a mistake of the cardmakers. In early versions they are always human figures, rising or falling in the world as the wheel turns: the mistake derives from the ass's ears or tail that signified the folly of their ambition. The other cards requiring explanation are the hermit and the hanged man. The hermit was called il vecchio or il gobbo in the early sources. He carried an hourglass instead of a lantern, though this mistake dates back to the late fifteenth century. Teofilo Folengo calls him il tempo, and Time was what he was originally intended to represent. The hanged man was sometimes called l’impiccato and sometimes il traditore. He is shown hanging upside down by one foot, a posture in which traitors were depicted. The walls of the Bargello in Florence were often adorned by such paintings. and the pope ordered the condottiere Muzio Attendolo. Francesco Sforza's father, to be so represented on all the gates and bridges of Rome: Ludovico Sforza (il Moro) gave a similar order concerning the treacherous governor of Milan. Bernardino da Corte. who surrendered the Castello to the French.

The final sequence represents spiritual and celestial powers: the devil, the tower, the star, the moon, the sun, the world, and the angel. The angel is the angel of the Last Judgment. On early cards the world is usually represented by a globe held aloft by putti or supporting a figure. There is no constancy in the representation of the three celestial bodies: extraneous details of all kinds are depicted on the lower halves of the cards. The puzzling card is the tower. This again is a modern name: in early sources it is called la saetta, il fuoco, la casa del diavolo. and l'inferno. In the celebrated French version of the pack known as the tarot de Marseille, it is oddly named la maison dieu. which may have resulted from a misunderstanding of la casa del diavolo. The card usually shows a building being struck by lightning or on fire and collapsing. In some late fifteenth-century versions, the building is in fact a tower. Without these earlier examples. one might be tempted to suppose that an event of 1521 led to a reinterpretation of the card. In that year one of the towers of the Castello Sforzesco in Milan suddenly collapsed, killing many French soldiers: lightning was said to have struck out of a clear sky. Soon after, the French were expelled from Milan. In a few versions of the card. the building is a hell-mouth, from which a devil emerges to drag a woman into hell; but this does not appear to represent the original meaning of the card.” [Pg. 46-47]

To summarize, Dummett saw the fool as it’s own thing, followed by 1-5 as the first group. Dummett didn’t give a collective description for this group but Waite described it as ‘of the conditions and estates of man. The second group, 6-14, represents ‘the condition of human life’. And the last group, 15-21, represents the ‘spiritual and celestial powers.’

Many occultist authors had noted the 3 part structure, going all the way back to the Comte de Mellet but also including Papus, Stanislaus Guita, Oswald Wirth and i’m sure many others as well. Many of these theories saw a three part structure in the significance they ascribed to the number 7 while Dummett’s finding was based on the discernable differences of subject matter between each division. Despite this breakthrough, Dummett was ultimately unable to see the big picture as he was still undecided about the placement of the virtues as late as 2004.5

Chronologically, the next book I would like to discuss is John Shephard’s The Tarot Trumps: Cosmos in Miniature (1985). This book is important to this survey as one of the few times that a new theory was proposed. Unfortunately, this book is not online and thus I haven’t read it, though I have read many summaries, reviews and opinions. The author was an astrology expert that wanted to try his hand at tarot iconography. As this is an astrology theory, my biggest question is if this book makes the Fool/Orion connection. From what I have read his main theory involves the Children of the Planets woodcuts. While I am familiar enough with this concept, I’d still like to read Shephard’s arguments in their full context.

Have you read this book? What did you think about it? Does he make the same Orion connection? Let me know your thoughts on this below, and if you have any questions or comments on this or any of the other topics we discussed. Thank you for reading and I will see you again next time.

Ronald Decker,

The Esoteric Tarot: Ancient Sources Rediscovered in Hermeticism and Cabala (2013) [Pg. 125] *page number from ebook

Michael J. Hurst, pre-gebelin.blogspot

Ibid.,

Michael Dummett, Where do the Virtues go?, The Playing-Card, Vol. 32, No. 4 (2004)

pre-gebelin.blogspot

Thank you so much for these fascinating posts!

Thank you for these posts ! After reading a few books on the subject, I am astounded at how much we DO know and how much we DO NOT know. The tarot is such an interesting object : constrained by its structure and subtle and infinite in its adaptation to the human mind. What works, works. And boy, does it work !